A Town Called Vardaman

There is not another town in America named after a more reprehensible human being than Vardaman, Mississippi.

I have started a new campaign (while I wait for my other campaign to gain traction). Quixotic campaigns, I suppose, are a hobby of mine.

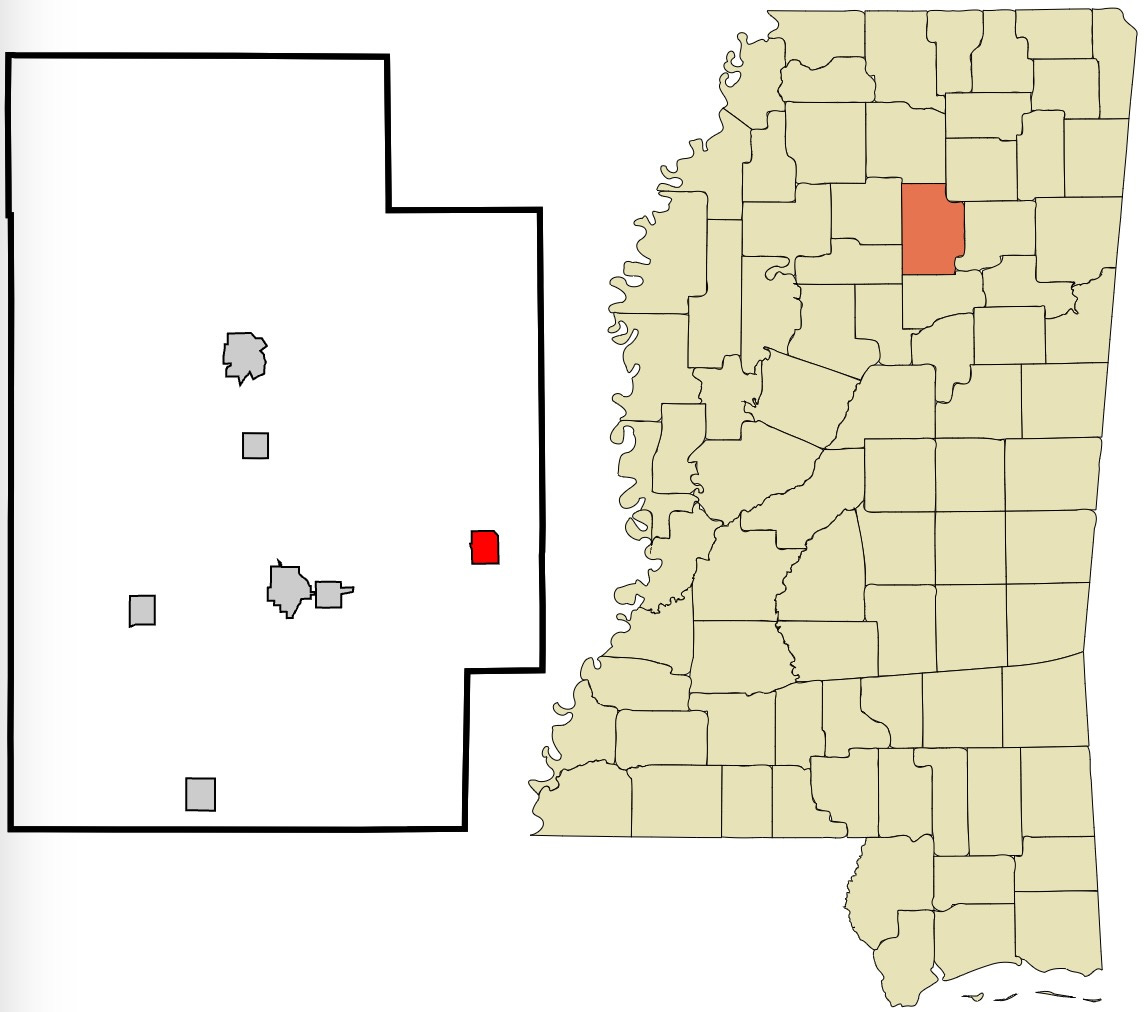

This new campaign concerns a town in north central Mississippi called Vardaman (pop. 1,100). Vardaman was founded in 1904 and named in honor of the state’s governor at the time, James Kimble Vardaman Sr. (1861–1930). Vardaman, who later served as a United Staes senator, was, even by the standards of early 20th century Mississippi politicians, virulently racist.

Nicknamed “The Great White Chief,” Vardaman was famous for his flowing locks and penchant for white suits. He won elections by appealing to poor whites, by stoking their fears and prejudices—and by making sure Black people didn’t vote. As a young state lawmaker, Vardaman helped write Mississippi’s 1890 constitution, which disenfranchised Black voters under the guise of election integrity. All voters were struck from the rolls and could only be registered anew if they paid a two-dollar poll tax and passed a “literacy test” administered by a registrar, who, invariably, passed the whites and failed the Blacks. Within a decade, the number of Blacks registered to vote in Mississippi fell from 130,000 to 1,300.

By cleverly avoiding the mention of race, Mississippi’s racist constitution survived numerous legal challenges and served as the template for other states intent on disenfranchising Blacks, including Oklahoma and South Carolina. “Mississippi's constitutional convention of 1890 was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the nigger from politics,” Vardaman bragged. “When that device fails, we will resort to something else.”1

Vardaman owned the Greenwood (Miss.) Commonwealth, a newspaper in which he made his views plain. “The Commonwealth is opposed to injecting any more niggers, chinamen and other mongrel races into the body politic of this country,” he wrote in an editorial, “with all the accompanying evils—bublonic [sic] plague, leprosy, ignorance and superstition.”2

Vardaman opposed public education for Blacks, called for the repeal of the 14th and 15th Amendments, and spoke favorably of lynching. “If it is necessary every Negro in the state will be lynched,” he once said, “it will be done to maintain white supremacy.”3

Today the population of Vardaman, Mississippi, is 39 percent white, 32 percent Latino, and 26 percent Black. I wonder how the nonwhite majority feel about living in a town named after a man who advocated white supremacy. For that matter, I wonder how the whites feel about it.

Governor Vardaman had a running feud with President Theodore Roosevelt, especially after Roosevelt dined with Booker T. Washington in the White House in 1901. Vardaman called Roosevelt a “coon flavored miscegenationist”4 and even managed to insult the president’s mother:

It is said that men follow the bent of their genius and that prenatal influences are often potent in shaping thoughts and ideas of after life. Probably old lady Roosevelt, during the period of gestation was frightened by a dog and that may account for the qualities of the male pup which are so prominent in Teddy. I would not do either an injustice but am disposed to apologize to the dog for mentioning it.5

In 1904, Vardaman’s founders asked the post office department to establish a post office in the town. TR’s postmaster general, Henry C. Payne, agreed to the request, but refused to allow the post office to be named after the governor. Citing his “statements concerning the mother of the President of the United States,” Payne said he “did not esteem it proper to give a post-office the name of any man who had used such language regarding any woman.”6 Payne ordered the town’s post office be called Timberville, an allusion, no doubt, to TR’s famous “big stick.” On their stationery, businesses in the town were compelled to identify their location as “Vardaman, Miss. (P.O. Timberville).”7

The town had two names until 1912, when TR’s successor, William Howard Taft, who had his own feud with the former president, finally allowed the post office to be called Vardaman.

Right now, there is not another town in America named after a more reprehensible human being than Vardaman, Mississippi. Of course, just because a town is named after a racist, that doesn’t mean its residents are racist. In fact, I suspect most residents of Vardaman today are unaware of the origin of their town’s name. I would love to go there and find out. It could make for an interesting podcast (dibs).

In 2017, the University of Mississippi pledged to rename a campus building named in James K. Vardaman’s honor after a committee found that he “actively promoted some morally odious practice, or dedicated much of [his life] to upholding that practice.”8 But apparently the university has encountered resistance, because, more than seven years later, Vardaman Hall still stands, its name unchanged.

Changing the names of long-established institutions is never easy, and the impulse to oppose name changes is understandable. There is history in names, even the offensive ones. But I have come up with, if I do say so myself, a rather clever workaround for Vardaman, Mississippi. You see, Governor Vardaman’s son, James Kimble Vardaman Jr. (1894–1972), was, unlike his father, a genuine American hero.

You can probably guess where I’m going with this.

Vardaman Jr. distanced himself from his father, philosophically and geographically. As a United States senator, Vardaman Sr. opposed America’s entry into the First World War, while Vardaman Jr. joined the Army and served with an artillery unit in France. After the war, Vardaman Jr. moved to St. Louis, where he worked in banking and manufacturing. He also joined the Missouri National Guard, where he met another veteran of the Great War, Harry S. Truman of Independence, Missouri.

Vardaman retired from the National Guard, but, with another world war on the horizon, he joined the Naval Reserve in 1939, at age forty-five. He saw combat in Algeria and Sicily, and was wounded in the latter when an enemy shell exploded near him. For his service he was awarded the Legion of Merit, Purple Heart, and Silver Star.

In 1945, Truman, now president, summoned Vardaman to the White House, where he served as the president’s naval aide, the first reservist to hold the position. Vardaman was by Truman’s side when he met with Churchill and Stalin at Potsdam. Vardaman’s father, who died in 1930, would’ve been alarmed to see his son working so closely with the president who would integrate the U.S. armed forces.

After the war, Vardamn served twelve years on the Federal Reserve System’s Board of Governors, helping to guide the American economy to unprecedented heights.

So, to rid itself of the stigma attached to the man for whom it is named, Vardaman, Mississippi, doesn’t even have to change its name; it can simply change its namesake. No need to get new signage or stationery or update the logo on the police cars! It’s not unprecedented, either: King County, Washington, has changed its namesake from William R. King (1786–1853), a slaveowner, to the civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968).

James K. Vardaman Jr. was far from perfect—Truman apparently thought he became a little too ambitious once he got to Washington, that he contracted “Potomac fever”—but he is objectively more worthy than his father of having a town named in his honor.

I recently sent letters to Vardaman’s mayor and aldermen, laying out my argument and urging them to vote to change the town’s namesake from Vardaman Sr. to Vardaman Jr. I’m not optimistic the letters will yield a result, but it’s worth a shot. If I get a response, I will let you know. In the meantime, if anybody has any suggestions on other ways to make this change happen, please message me.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1324271

https://books.google.co.bw/books/about/The_White_Chief_James_Kimble_Vardaman.html?id=71CrpwAACAAJ&redir_esc=y

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/flood-vardaman/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/27550103

https://www.jstor.org/stable/27550103

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-courier-journal-tr-vetoes-vardaman-p/118711564/

https://books.google.co.bw/books/about/Vardaman_Mississippi_History_and_Memorie.html?id=sJomzgEACAAJ&redir_esc=y

https://www.oxfordeagle.com/2017/07/06/ole-miss-will-rename-vardaman-hall-contextualize-several-campus-spots-tied-to-confederate-history/

Kinda interesting that he would bring Mitty Roosevelt into it. It's my understanding that she was super Confederate. When she disciplined Theodore and he felt wronged, he would pray loudly and fervently that the Union troops would "grind the southern troops into powder". Though, as I'm typing this... I realize I learned that from a book that I had a few gripes with. It also referred to Chester Arthur as "decent and incorruptible." 😅

Good luck with your mission!